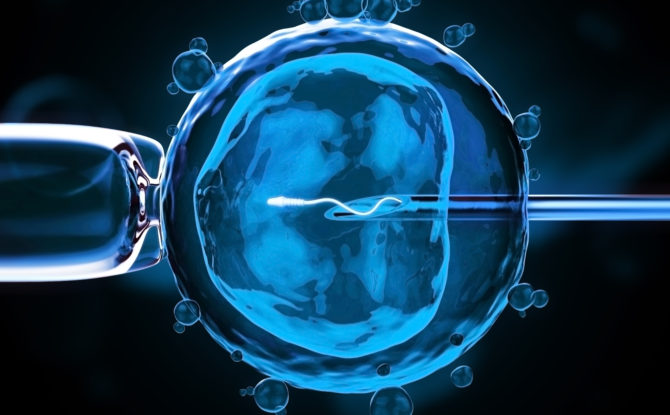

IVF Does Not Raise Breast Cancer Risk, Study Shows

Women undergoing in vitro fertilization have long worried that the procedure could raise their risk for breast cancer.

After all, the IVF treatment requires temporarily increasing levels of certain sex hormones to five or 10 times the normal. Two of those hormones, estrogen and progesterone, can affect the course of certain kinds of breast cancer.

A series of studies over the past decade suggested that these former patients may have little to worry about. Experts remained cautious, however, because women who had undergone IVF in the 1980s had not yet reached menopause by the time of the research.

But the largest, most comprehensive study to date, published on Tuesday, provides further reassurance: It finds no increased risk among women who have undergone I.V.F.

“The main takeaway is there’s no evidence of an increased subsequent risk of breast cancer, at least in the first couple decades,” said Dr. Saundra S. Buys, an oncologist at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, who was not involved in the new study.

The issue has nagged at specialists in reproductive medicine for some time. In 2008, a retrospective analysis of medical records, which the authors called “preliminary,” found a potential increase in breast cancer among IVF patients older than 40.

Another small study of participants at a single treatment center in Israel reported an increased risk of breast cancer among women who start IVF after 30.

Maddeningly, later findings went the other way, seeming to suggest the danger — if there were one — may be greater for younger women.

A study with roughly 21,000 participants, published in 2012, found that women in Western Australia who began I.V.F. at 24 years old or younger had an increased risk of breast cancer. No such link was found among women in their 30s or 40s.

In 2013, though, researchers published a meta-analysis of eight smaller studies tentatively suggesting that I.V.F. didn’t seem to raise breast cancer risk overall.

But it did not rule out the possibility that breast cancer might turn up in a bigger group of women tracked more closely for an even longer period. Experts also worried that infertility itself, not only its treatment, might somehow be linked to breast cancer.

Today’s report, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, goes a long way toward answering the lingering questions.

by Catherine Saint Louis

New York Times, July 19, 2016

Click here to read the entire article.