South Jersey Times – February 9, 2015 by Andy Polhamus

A lesbian couple from Salem County are locked in a custody battle over their son after a sperm donor sued them for parenting time.

The outcome of their case, according to their attorney and a Rutgers law professor, might change the status of reproductive rights for couples around New Jersey who conceive by artificial means.

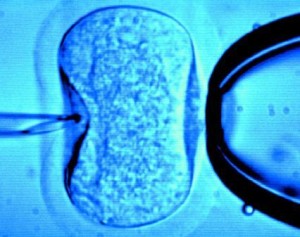

Sheena and Tiara Yates of Pennsville had a son who was conceived by at-home artificial insemination — known colloquially as alternative insemination — in June 2013 under the counsel of a physician. The couple already had a toddler, also conceived by artificial insemination from a different donor, and had drawn up contracts in which both men relinquished their legal paternity.

It looked for a while as though everything had gone smoothly. In the same five-month span between December 2013 and April 2014, however, both sperm donors came forward and filed for visiting rights with each child.

State law addressing artificial insemination and domestic issues, as the Yateses discovered, says that only when the insemination process is carried out under the direct supervision of a physician, can the non-biological parent be legally considered the natural parent of the child. The law also protects the donor from having any “rights or duties stemming from the conception of the child.”

The Yates family lost the first custody case, and that donor now has visitation time with the older child — a court ruling the couple decided not to dispute. The same thing happened with the second suit in September after a Salem County Superior Court judge ruled in favor of the donor, Shawn Sorrell. His parenting time begins with a few hours each weekend in addition to paying $83 a week in child support.

“Emotionally it’s very hard for us,” said Sheena Yates. “All we want is a family, and we can’t have kids without an outside party. It’s a lot for us to have to deal with. It’s not just hard on us, it’s hard on the kids, too.”

The Yateses asked that their children’s names not be revealed to protect their privacy.

The couple’s son is now a year old, and according to Sheena, had not met his biological father until visitation began. Sorrell, of Wilmington, Delaware, is representing himself in the case. He could not be reached for comment.

As they file their appeal with the Superior Court of New Jersey’s appellate division, the Yateses not only argue that the precise location of the procedure should be irrelevant, but also hope one major factor will influence an appellate court’s decision about custody over their younger child. They had no legal recognition of their relationship when their first child was born, but have been in a civil union since 2011 and got married in May 2014.

“The question now is whether the presumption of marriage is stronger than the artificial insemination statute,” said Kimberly Mutcherson, a professor of law at Rutgers-Camden. “You’re battling out two different parts of the statutory scheme and figuring out which one would prevail.”

Without the marriage aspect, she added, the case would be fairly cut and dry.

“It’s a core mistake people make. The court says if you go to a physician and do it their way, [donors] don’t have a legal connection to the child,” Mutcherson said. “When you don’t have that anymore, you have two people on equal footing. At that point it’s just a custody proceeding.”

John Keating, the Glassboro-based attorney representing the Yateses, said he hopes the question of marital status will strengthen their case.

“We think it’s important the appellate division make a decision. Our purpose here is for other couples not to go through this. They set out to start a family together, and they did what they thought was the right thing,” he said. “They entered into contracts with sperm donors, they consulted a physician and are now in a position of raising two children with two sperm donors instead of being two parents and their children. Now there are four parents raising these children.”

Sheena said she hopes bringing attention to her case will help other couples avoid similar problems in the future.

“It’s not just us,” she said. “It’s thousands of others who could go through it, too, and it affects people’s lives every day.”

Keating also argues that their consultation of a physician should hold up in court, despite the fact that the procedure was carried out at home. Furthermore, he said, the court’s interpretation that artificial insemination must be carried out only by a doctor puts lower-income people, gay or straight, at a disadvantage. Fertility clinics carry a hefty price tag, and sperm banks aren’t cheap.

“We don’t think this is an anti-LGBT decision,” Keating said, but noted that even initial fees at most sperm banks tally about $1,000. “But we do think it disparately impacts LGBT couples, and disproportionately impacts lower-income people.”

Mutcherson agreed.

Click here to read the entire article.

I call them my daughters because I am their biological father through sperm donation, but the truth is that I am not their parent. This is a critical distinction that any donor dad must make. I am not a co-parent with my daughters’ mothers. But that doesn’t mean that I do not have a meaningful and reciprocally fulfilling relationship with them, it just means that the major life decisions that relate to my girls are made by their mothers, the two amazing women who taught me how to be a dad.

I call them my daughters because I am their biological father through sperm donation, but the truth is that I am not their parent. This is a critical distinction that any donor dad must make. I am not a co-parent with my daughters’ mothers. But that doesn’t mean that I do not have a meaningful and reciprocally fulfilling relationship with them, it just means that the major life decisions that relate to my girls are made by their mothers, the two amazing women who taught me how to be a dad.