Ever since the tragedy in Florida, many are asking, how do gay parents explain Orlando to their kids?

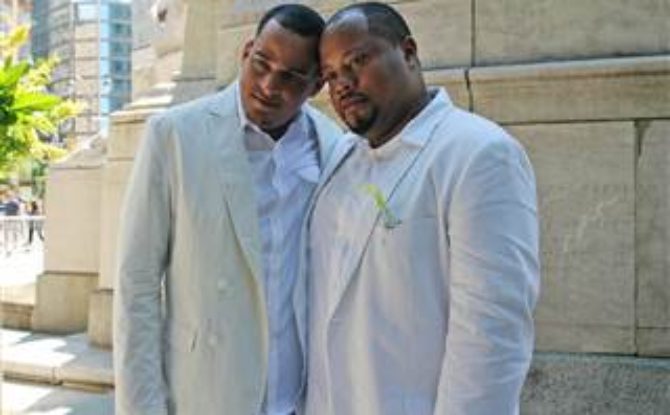

Today’s column is written with a sense of emergency. The baffling massacre in Orlando has insinuated itself into me in unexpected dimensions, and caused me to ask all kinds of questions that, amazingly, I’d managed to sidestep until now. How do gay parents explain Orlando and talk about violence against LGBTQ people? What can I do differently, if anything, to keep them safe when the toll of violence is made so clear? How do I balance talking about uncertainty with the need to reassure them? And, perhaps most troubling, how do I deal with this fact: My fear for my children is bound up in my fears for myself, usually safely stowed in the overhead compartment but subject to falling out when I encounter unexpected turbulence. (I should add here that I don’t have to create or answer these questions on my own; I have a level-headed husband who’s been just as involved in working through this mess.)

I’ve been a regular contributor to Slate for years, but an introduction seems in order. This will be the first in a series of monthly columns I’ll be writing on one type of parenting: ostensibly, gay parenting, but more accurately, just my own up-and-down efforts at the task. Tolstoy’s opening line in Anna Karenina is famous but wrong—all families, not just the unhappy ones—are unique. So while the pieces will run each month in this Outward blog, any broader lessons that might be drawn for LGBTQ families—let alone other families—will be some combination of luck and the (soon-to-be-legion) readers’ own connections to whatever I happen to be discussing.

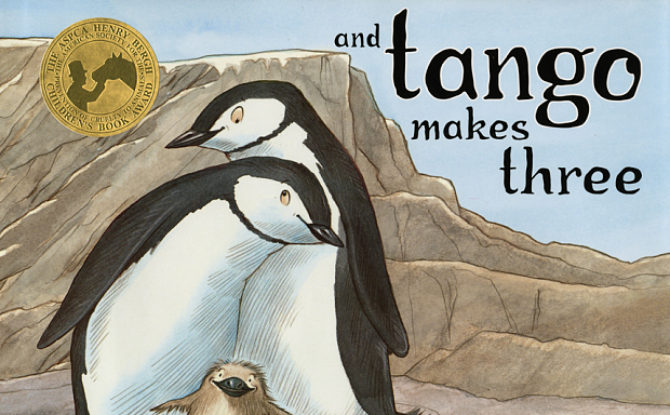

My kids have been lucky so far. They haven’t had to deal with any of the bullying and collateral trauma that their fathers did, and, in our progressive Philadelphia community, our family structure hasn’t caused them any problems, either. So figuring out what to say to them about violence against LGBTQ people is quite different from, say, the anguishing task Ta-Nehisi Coates set for himself in Between the World and Me. Though he recognizes the generational changes that complicate understanding his son’s experience, his eloquent, heartbreaking account of the thousand natural shocks to which African American bodies are heir is their shared, lived reality.

Our kids, by contrast, are usually safe—to the extent that any kids are safe, at least. That makes explaining anti-LGBTQ violence a different kind of challenge. They’ve had infrequent, and mostly painless, reminders of the stubborn fact that their family is different. Here’s a memorable example:

Scene: Coffee shop, circa 2010. An early Saturday morning. Me, alone with the kids.

Waitress: “Oh, is it mom’s day to sleep in?”

Kids, age 6 [in chorus]: “We don’t have a mom. We have two dads.”

Waitress, not missing a beat: “Wow, you’re lucky! I don’t even have one dad, and you have two!”

See? Kind of a positive experience.

So when Orlando happened, we were starting from zero. Our kids have no experience with fear or rejection of their family. They’re much less at risk, it seems, than we were as children. (I mostly avoided being bullied, but only through a series of baroque stratagems, the creating and sustaining of which imposed their own costs.) But we needed to talk about the incident, especially since we were taking them to a vigil to mourn and mark the event, collectively.

We found ourselves explaining how and why some madman would even want to harm gay people. A simple script seemed sensible: Most people, as you know, treat gay people the same way they treat everyone else. A few people still don’t like gays, though. And a very, very tiny number of people, with serious mental health problems, do crazy, horrible things like what happened over the weekend in Orlando. (From what I understand, the daily CNN news report the kids consume in school discussed the massacre on Monday, but, incredibly, the teacher didn’t follow up the harrowing broadcast in any way.) We opted for reassurance over nuance.

by John Culhane, Slate.com – June 14, 2016

Click here to read the entire article.